Are nations thinking, and acting, for the long term?

Six years after signing up to sustainable development and climate action, are countries’ plans fit for purpose to make long-term change?

Data and monitoring — Global

In 2015, UN Member States adopted the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Paris Agreement on climate change, with objectives to be achieved by 2030 and 2050 respectively. The COVID-19 pandemic is a clear setback. But governments all over the world should not lose sight of the long-term objectives they signed up to in 2015. First, because achieving the SDGs and the Paris goals will help prevent and respond to those low-probability, high-cost events such as pandemics that will inevitably strike again. And, second, because there is nothing in terms of technology or finance that says that goals cannot be achieved.

The SDGs and the Paris Agreement provide the vision for ‘building forward better.’ Yet, despite some progress on the SDGs since 2015 and increased country commitments to achieve climate neutrality by mid-century, governments’ actions and investments so far have not been transformative enough to achieve internationally agreed targets for sustainable development. This is particularly true in G20 countries, responsible for 75% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

Yet achieving the SDGs and the Paris goals requires accelerated actions and leadership from G20 countries, especially on the energy and climate transition. This in turn needs a stronger focus on benchmarking: not only comparing outcomes and commitments but also aligning government actions, such as investments, subsidies, and regulations, to achieving the goals.

The pandemic has stalled progress on the SDGs

Before the pandemic hit, the world was making headway on sustainability and climate action. But the pace was insufficient in all countries, and no UN member state was on track to achieve all the SDGs.

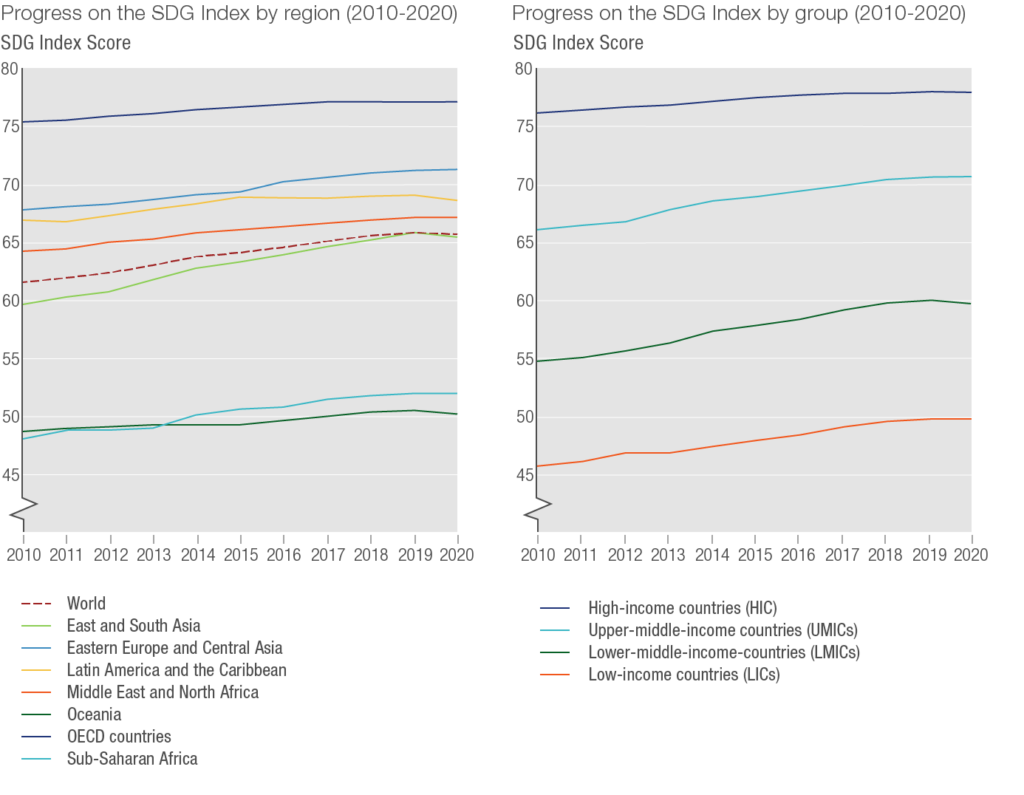

Every year, SDSN and the Bertelsmann Stiftung publish the SDG Index and Dashboards. These track the performance and progress of all UN Member States on the 17 SDGs. The global SDG Index is based on 85 outcome indicators such as prevalence of extreme poverty, life expectancy, literacy rate, CO2 emissions, and homicide rate. The 2020 edition underlined that before the pandemic hit, on average, every UN region and country income group was making progress towards the SDGs. To a large extent this was driven by gains on socio-economic goals, including SDGs 1 to 9 that cover access to basic services and infrastructure.

Yet, the pace was not fast enough to achieve the SDGs by 2030. Some goals, especially SDGs 12 to 15 on climate and biodiversity, SDG 2 on sustainable agriculture and diets, and SDG 10 on reduced inequalities, did not show significant progress in many parts of the world, including in highly populated countries such as the G20.

Frustratingly, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to reversals in progress on many key SDG indicators.

Figure 1: progress on the SDG Index from 2010 to 2020 by region and country income group

Source: Sachs et al, 2021

The gap between long-term commitments and transformative actions

Due to time lags and data gaps in international statistics, it is important to also assess government commitments and pledges as well as their actions to gauge whether countries think and act for the long term. At the international level, outcome statistics are often three years old or more by the time they are published. Also, looking at past growth rates to estimate future trajectories may not reflect accurately the introduction of transformative policies and actions. Benchmarking commitments and observable actions provides more forward-looking approaches to estimating countries’ level of ambition for achieving long-term goals.

Estimating government commitments and actions for the SDGs and the Paris goals remains a difficult exercise. It relies on qualitative data (laws, regulations, policies, and so on) that are not standardized internationally, and on expert judgment. Yet, available data suggest that commitments and actions for the SDGs in G20 countries are largely insufficient, including on energy decarbonization, sustainable industry, and the objectives of the Paris Agreement.

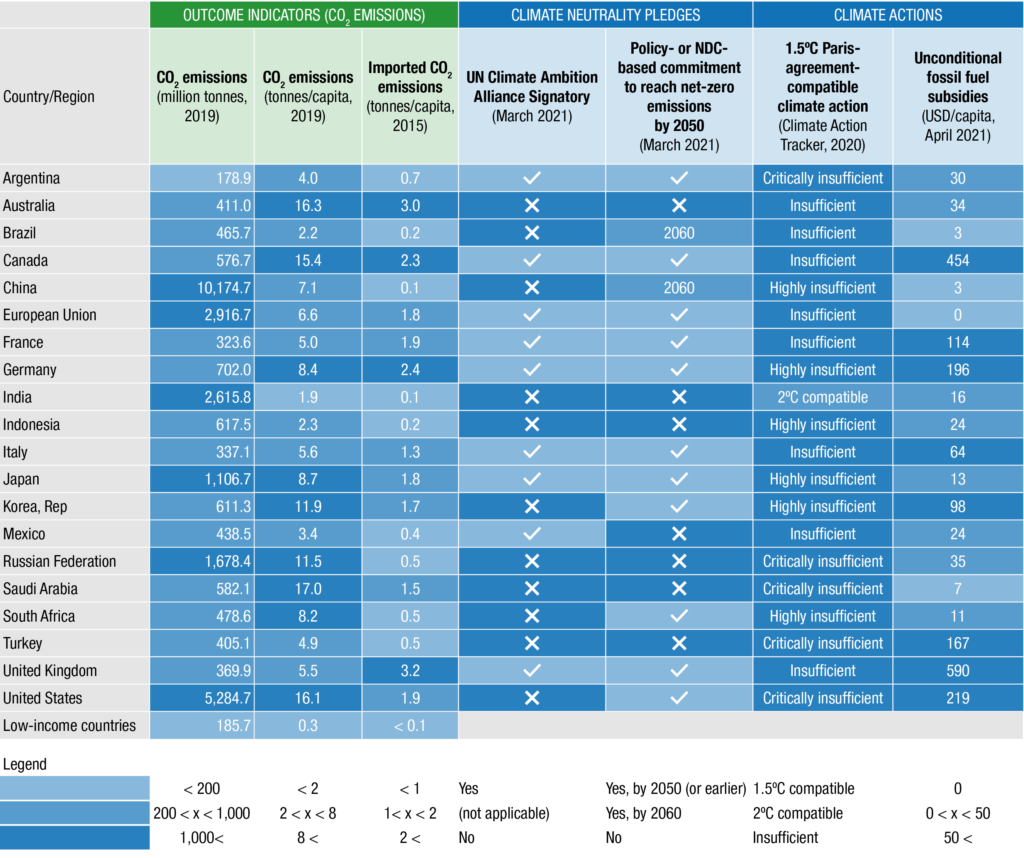

Table 1 (below) shows that G20 countries are responsible for the bulk of CO2 emissions in both absolute and per capita terms. Besides Brazil and India, no G20 country is close to achieving the target of two metric tons of CO2 emissions per person per year that is needed to limit global temperature rise to 1.5°C by 2050. The observed decline in in CO2 emissions observed in some G20 countries since 2015 remains largely insufficient. Through consumption, many G20 countries also generate CO2 emissions abroad (so-called ‘spillovers’). These include outsourcing the production of cement or steel, equivalent to three metric tons per person per year or more in Australia and the UK.

Table 1: CO2 emissions v climate pledges and actions in G20 countries

Note: Population-weighted average for low-income countries.

Source: Authors. Based on Sachs et al, 2021

As of this writing in April 2021, six of the G20 countries have made no significant commitment to achieving climate neutrality by mid-century. Under the leadership of the governments of Chile and the UK, and with the support from UN Climate Change and the UN Development Programme, 121 countries (as of March 2021) have joined the Climate Ambition Alliance. The alliance aims to “push for net-zero CO2 emissions in line with latest scientific information.” According to the Net Zero Tracker, 32 countries have included a net-zero emissions target either in national law, proposed legislation, or a policy document. At the Leaders’ Summit on Climate convened in April 2021 by the US administration, President Biden urged world leaders to accelerate efforts on climate actions.

In 2019 the European Union adopted its climate neutrality target (by 2050) via the European Green Deal. In 2020, several G20 countries, including Canada, Japan, South Korea, the US (all by 2050), and China (by 2060) committed to net-zero emissions. Meanwhile, Australia, India, Indonesia, Russia, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey are neither signatories to the Climate Ambition Alliance nor have committed in national policy documents to achieving climate neutrality by mid-century.

Despite these commitments and pledges for climate neutrality, government actions remain largely insufficient. The Climate Action Tracker (CAT) is a scientific evaluation tool developed by a research consortium specialized in the field of climate mitigation. It evaluates both the content of nationally determined contributions (what governments propose to do) and current policies (what governments are actually doing) to meet the objectives of the Paris Agreement. The latest CAT assessment covers 32 countries, including all G20 countries, and the European Union. No G20 country is considered to have aligned its actions to achieving the 1.5°C objective of the Paris goals. According to Energy Policy Tracker, G20 countries continue to provide unconditional fossil fuel subsidies in COVID-19 recovery packages. In eight of the G20 countries, these subsidies exceed $50 per person of the population. Vivid Economics and Oxford University’s Global Recovery Observatory also emphasize the lack of ‘greenness’ in most G20 countries’ recovery packages.

Four public governance priorities for achieving long-term goals

Looking ahead, we identify four public governance priorities for accelerated actions in both G20 and other nations.

First, countries need to emphasize long-term planning with support from science, engineering, and public policy. Countries should consider medium-term targets with time horizons of 10 to 30 years (that is, 2030 for the SDGs and 2050 for the Paris Agreement) and develop policy pathways for achieving them. In the context of the SDGs, the SDSN has proposed six SDG transformations that consider synergies and trade-offs across the SDGs and the institutional set-up within governments. Long-term pathways and backcasting exercises (working backwards from a desired future outcome to define the path to achieve it) can be done focusing on these transformations (or adjusted versions of them, depending on countries and context).

Second, budgetary frameworks and financing must be aligned with these long-term pathways to strengthen public investment in the SDGs alongside private financing. According to various estimates, the ‘greenness’ of stimulus packages varies extensively from country to country, both in size and level of ambition. Private financing should also be further mobilized for the SDGs. The new EU taxonomy regulation for sustainable development that came into force in July 2020 is a promising effort towards redirecting capital flows into sustainable projects.

Third, SDG transformations can only succeed if they enjoy societal legitimacy. Political processes should engage the public in participatory decision-making and promote transparency and accountability. Recent engagement processes launched in France and the UK (among others) are moving in the right direction.

Fourth, global challenges and risks require global cooperation and responses. The COVID-19 pandemic and emergence of new variants highlighted that no one is safe until everyone is safe, calling for international collaboration to accelerate mass vaccination for all. In a globalized and interconnected world, pandemics, climate change, cybersecurity threats, and other economic and social shocks cannot be managed by countries working independently. As the world recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic, strengthening multilateralism and UN institutions, including early-warning and monitoring systems, are key priorities for accelerated actions on the SDGs and the Paris Agreement.