The elusive goal of equality

“Leave no one behind,” the central tenet of the SDGs, underlines the importance of tackling inequality as countries strive to achieve the Global Goals. Rampant inequality is connected to setbacks in other areas, from democratic backsliding and the weakening rule of law to sluggish action on climate

Economic development

In 2015, all UN Member States committed to reducing inequalities as part of the Sustainable Development Goals. SDG 10 calls on countries to reduce inequalities within their borders and across countries. On the 10th anniversary of the SDGs, data from the Sustainable Development Report (SDR) 2025 shows that progress on SDG 10 has been mixed: while some countries are on track, most are stagnating or displaying limited progress, and some countries even show increasing levels of inequality. As millions face rising hunger and food insecurity while the number of billionaires reaches record highs, combating inequality remains as urgent a priority as ever.

The state of inequality – 10 years on from the SDGs

The SDR 2025 uses the Gini coefficient as one of the leading indicators for measuring inequality in countries. Gini measures the degree to which economies deviate from perfect equality, with higher values representing greater inequality. While it tends to underestimate inequality in countries due to underrepresentation of top incomes in household surveys, it is a useful tool for gauging how inequality differs across countries and how it evolves over time.

Figure 1: progress toward meeting the target on SDG 10: Gini coefficient, SDR 2025

Source: SDR 2025 and World Bank

As figure 1 shows, among the 78 countries for which sufficient time series data was available from the World Bank to calculate trend evaluations since the start of the SDGs:

- one-third are on track for meeting the target

- 52% are showing limited progress or stagnating

- 15% are moving in the wrong direction

This last category of worsening inequality includes some major economies such as Brazil, Colombia, and the United States.

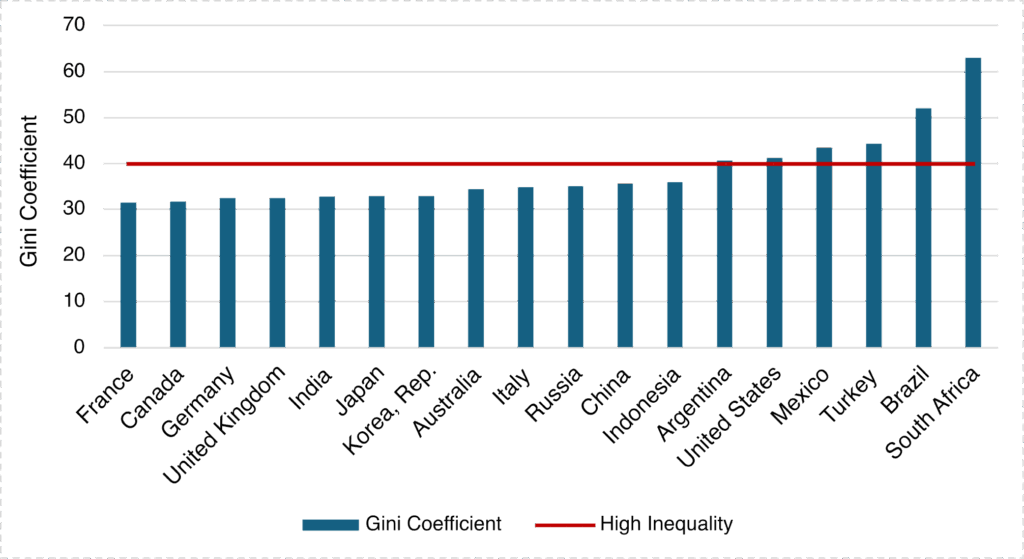

It is difficult to generalize about global trends, as progress varies widely across countries. Figure 2 offers a deep dive into the distribution of the series, restricting the observations to G20 countries.

Figure 2: Gini coefficient in G20 countries, latest available year

Source: World Bank (note: data missing for Saudi Arabia)

Among G20 countries, there is a significant degree of dispersion. On the one hand, none of the G20 countries have Gini coefficients on a par with those of the Nordic countries (historically among the most egalitarian economies, with Gini coefficients all below 30). Most of the G20 countries fall between the 30 and 40 range, but Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, South Africa, Turkey, and the United States all have high degrees of inequality, defined here as a Gini coefficient above 40, with no signs of improvement (apart from Mexico, whose Gini has decreased). Globally, 30% of the 163 countries with available data have economies marked by high inequality. The verdict is clear: 10 years after the adoption of the SDGs, too many countries around the world continue to face high or rising rates of inequality.

Inequality is deeply linked with climate action, democracy, and rule of law

Rising inequality, and economic injustice more broadly, is not only a problem in itself. Addressing economic inequality across and within countries is also necessary for addressing climate change. The largest emitters of CO2 tend to be high-income countries. Within high-income countries, the wealthiest sections of the population account for far more emissions than the national average. For example, in France, a person in the highest income decile will emit at least four times more CO2 than the 10% poorest decile of the population. Meanwhile, those most vulnerable to the impacts of environmental degradation also tend to be the poorest: small island developing states (SIDS) face disproportionately more impacts from climate change despite little historical responsibility for causing climate change. Within countries, the poor also tend to be disproportionately exposed to the risk of air pollution mortality.

In addition to climate change, researchers have studied the link between inequality and democracy. In the context of democratic backsliding in the 21st century, researchers at the University of Chicago found that the biggest predictor among possible risks of democratic erosion was income inequality. The authors suggest this relationship may stem from the way in which inequality increases polarization and perceptions of unfairness in the way economic opportunity is distributed. While inequality alone cannot determine the strength of a democracy, it is worth noting that among the countries scoring highest on the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Electoral Democracy Index, all have low Gini coefficients (see table 1).

Table 1: countries scoring highest in the V-Dem Electoral Democracy Index

| Index score | Country | Gini coefficient |

| 0.92 | Denmark | 28.3 |

| 0.90 | Estonia | 31.8 |

| 0.90 | Ireland | 30.1 |

| 0.89 | Switzerland | 33.7 |

| 0.89 | Belgium | 26.6 |

| 0.88 | Norway | 27.7 |

| 0.88 | Sweden | 29.8 |

| 0.87 | Czechia | 26.2 |

| 0.87 | Luxembourg | 32.7 |

| 0.87 | France | 31.5 |

Source: V-Dem Dataset

Similarly, the rule of law, enshrined in SDG 16 (peace, justice, and strong institutions), also appears to be connected to countries’ levels of inequality. There is a negative correlation between inequality and the rule of law, as measured by the World Justice Project (WJP) Rule of Law Index. Table 2 shows the top and bottom 5 countries in the index and their associated Gini. Countries with the most effective rule of law also tend to display lower levels of inequality.

Table 2: top 5 and bottom 5 countries in the WJP Rule of Law Index

| Overall score | Country | Gini |

| 0.90 | Denmark | 28.3 |

| 0.89 | Norway | 27.7 |

| 0.87 | Finland | 27.7 |

| 0.86 | Sweden | 29.8 |

| 0.83 | Netherlands | 25.7 |

| —————— | ||

| 0.26 | Venezuela | 44.7 |

| 0.33 | Haiti | 41.1 |

| 0.34 | Myanmar | 30.7 |

| 0.34 | Congo, DRC | 44.7 |

| 0.34 | Nicaragua | 46.2 |

Source: WJP Rule of Law Index

Closing the gap through policy

Legislative action and government policy play a major role in how inequality evolves over time. To measure how effectively governments tackle inequalities, the Commitment to Reducing Inequality Index, compiled by Oxfam, evaluates government action on three primary policy levers:

- spending on public services, such as health, education, and social protection

- the progressivity of the tax system (whether the rich pay their fair share in taxes)

- labor rights and wages (whether the government protects against precarious employment)

It is no surprise that Norway tops this assessment, followed by Canada – both countries with low levels of inequality and Gini coefficients below 30. Looking at trends over time, the report identifies countries that have improved the most by changing or introducing policies to reduce inequality. These include:

- Burkina Faso, for increasing its minimum wage and making value-added tax more progressive

- Croatia, for increasing public health expenditure and health coverage

- Paraguay, which has increased the share of formal employment, doubled the minimum wage, and raised health expenditure

These success stories underline that inequality is not inevitable but shaped by government choices and policies. That so many countries face rampant disparities is a stark reminder that governments are falling short on their SDG commitments and must act decisively to close the gap.

Featured in:

UNGA 2025 edition: Restoring hope

An effective multilateral response is needed for an ever increasing number of crises. At the same time, the UN – the heart of the multilateral system for 80 years – is under attack from nations trying to defund and disempower it. Radical reform is clearly needed. Whatever form that takes, it should be guided by and designed to support the SDGs.

This edition considers the impacts of inequality and conflict, and explores ways to build a fairer, safer future through education, technology, economic development and global partnerships.

Authors include Adriana E. Abdenur, Julia Bunting, Richard Gowan, Samira Rashwan, Shari Spiegel, Ariesta Ningrum, Grayson Fuller, Joanne Raisin, Susan Gardner and Roya Mahboob.

Publication date: 22 September 2025