Tackling poverty and hunger within planetary boundaries

To balance the combined pressures of climate change and growing populations, we need to re-evaluate what we eat and where and how it’s grown

Food systems and sustainable agriculture — Asia (Central, Eastern and Southern), Global, Sub-Saharan Africa

Imagine a world free of poverty (Sustainable Development Goal 1) and hunger (SDG 2). To achieve this ‘double zero’ within planetary boundaries (SDG 15) in the face of the visible impacts of climate change is perhaps the greatest challenge of our time.

It is also a challenge to which each one of us can contribute. We can change our diets and reduce the amount of animal-based products we consume. The amount of food lost at or after harvest, wasted along the value chain or left on our plates is shocking and must be reduced. Yet even the most conservative projections suggest we need to produce at least 20% more food to match global demand by 2050. Many even consider the world will need to increase food production by 50%. Clearly, more must be produced to match the demand for nutritious food for all. But where and how can this be achieved? And who are the farmers who will feed the world?

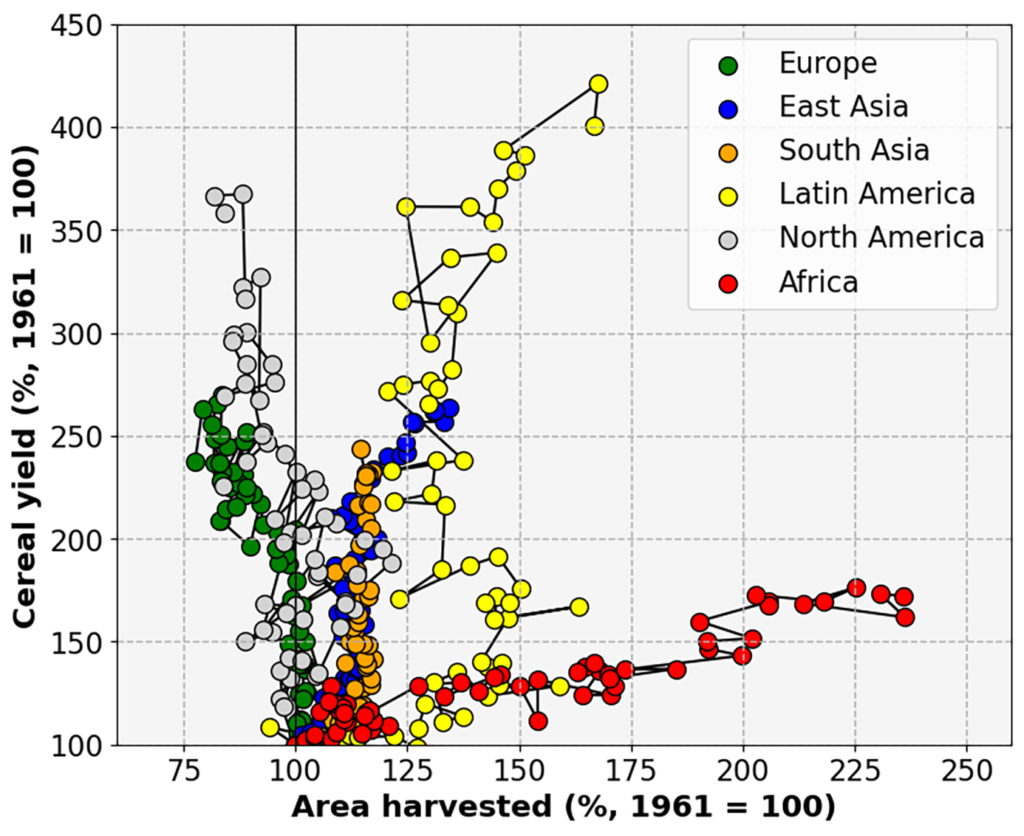

To understand where there are opportunities to produce more food, we can learn from how the world has kept pace with its growing human population until now. Over the past 60 years, yields of the major staple cereals have increased dramatically (Figure 1). Compared with 1961, we now produce up to four times the yield of cereals harvested per hectare in Latin America and roughly two and a half times as much in Europe and Asia. The area of cropland harvested has also increased strongly in Latin America and Asia, but by contrast has fallen in Europe. Yield increases in Africa have been more modest, where the food demand for the growing population has largely been met through the expansion of agricultural land and importing food. Rather than simply bemoaning the lack of past increases in crop productivity in Africa solely as a failure, we can also see it as an opportunity. It is an opportunity to understand why Africa has diverged from other regions, and an opportunity to increase crop yields in Africa and narrow yield gaps in future.

A tale of many continents

Figure 1: past intensification and area expansion trajectories of staple cereal production across different regions of the world. Data is shown in relation to the base year of 1961 and the lines track the trajectory from year to year (analysis by João Vasco Silva based on FAOSTAT

Before we consider these questions, let’s take a step back and reflect on the farmers who produce our food. The vast majority of farms globally are still family enterprises, although this is changing rapidly in many wealthier countries. The number of farms has fallen dramatically in Europe and North America where less than 2% of the population is involved in farming. The tight economic margins of food production lead to the continuing expansion of farm areas and a decline in numbers of farms. By contrast, there are around 500 million small-scale (less than two hectares) producers in low and middle-income countries, and the numbers continue to rise. When we consider their households, this means that between two and a half and three billion people depend, at least partly, on agriculture for their livelihoods. Many of these rural households are both poor and hungry, which is why SDG 1 and SDG 2 are inextricably interdependent.

So why has Africa fallen behind Asia in terms of crop productivity and outstripped it in the incidence of poverty? Many papers and books have been written on the success of the green revolution in Asia, which resulted from major government investment in rural development in general and cereal farming in particular. Many Asian countries have achieved food self-sufficiency based on their own production, as well as bringing down the incidence of poverty dramatically. Although many of the gains in crop productivity in Asia result from the opportunities for irrigation, which allows for several crops each year on the same land, this cannot explain all of the divergence in trajectories. Clearly the lack of consistent government investment in rural development in African countries has also played a major role.

If we look to the future, the population in Asia is starting to plateau. But in sub-Saharan Africa, populations continue to grow rapidly: UNDESA projects the population to increase by 305 million in the decade to 2030, rising to 1.4 billion. Across the African continent there is a burgeoning demand to provide nutritious diets for the rural and urban populations. We thus have a peculiar situation where there is a clear opportunity to increase crop productivity to meet this demand. At the same time there are several key problems to solve:

- achieving national food security

- tackling rural poverty through providing extra income for rural households

- providing extra employment throughout the food system

- reducing dependence on imports to help the balance of payments

The food security conundrum

Yet, sustainable intensification to narrow yield gaps is not taking off in Africa. Why? Because of the small and fragmented farm sizes, inadequate rural infrastructure, and the lack of an enabling socio-economic environment. This is what I have termed the food security conundrum of sub-Saharan Africa. The smallholder farmers who predominate are often ‘reluctant farmers’ who seek more remunerative employment opportunities off-farm.

To unpack the problem further, the underlying and pervasive problem that constrains agricultural productivity in Africa is the lack of soil nutrients. Although we should not underplay the importance of the climate crisis, which is exacerbating extreme weather events such as floods and droughts, tacking poor soil fertility is key. This is illustrated by the paradoxical situation where some of the most food-insecure regions are those with highly favorable conditions for agricultural production.

For example, the inherently fertile soils of the East African highlands where the bi-modal rains allow two cropping seasons each year attracted early settlement for agriculture. Rapid population growth and land subdivision over generations coupled with intensive cultivation with few inputs has exhausted the natural fertility of the soil and led to declining productivity. This gives rise to a double poverty trap of small farms and poor soils. By contrast, in some regions with drier climates and inherently poorer soils, but where populations are less dense and farms are larger, a much larger proportion of households are food secure.

So how can this food security conundrum be tackled? Raising food prices is not an option as affordable, safe, and nutritious food is needed for both the urban and rural poor. Also, many rural households are net buyers of food (they consume more than they produce). If we are to learn from Asian experiences, a whole raft of different approaches is needed to ensure stable incentives for producers and access to food for the poor. This is one important conclusion of an eDialogue: What Future for Small-Scale Farming that the Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN) hosted over several months in 2020 together with Foresight4Food, IFAD and APRA (Agricultural Policy Research in Africa).

We should not forget that many Asian countries still face major challenges. Figures from The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020 show that there are many more poor and undernourished people in Asia (1.03 billion) than Africa (674 million). In India, 70% of small-scale farms are ultra-small (less than 0.05 hectares) and yet are still important for families’ nutrition and livelihoods. What we call smallholder farmers are a very diverse group, but it is clear that many cannot make a living from farming alone. They depend on family members earning income outside the farm in many shapes and forms, from small-scale enterprises and rural wage labor, to jobs in urban areas.

Agriculture is a still a key source of smallholders’ food and income, so finding ways to increase productivity and farm incomes are key to addressing both poverty and hunger. How best to do this is a matter of debate. An attractive approach is based on sustainable intensification through diversification. By increasing crop diversity beyond the basic staples (cereals, roots, tubers, and bananas) to include more nitrogen-fixing legumes and vegetables, multiple benefits can be gained in productivity, soil fertility, and nutritious diets. Decades of underinvestment cannot be addressed without additional nutrients. Achieving this requires not just different crops, but also a focus on integrated soil fertility management to efficiently recycle nutrients within the farm through organic manures, and supplementing with inputs of nutrients through mineral fertilizers.

Solving the conundrum?

The big question at the heart of the food security conundrum is of course how to make all this happen. It is clear that African governments need to make firm commitments to tackle poverty in rural areas through investing in agriculture, and to create jobs to relieve the pressure on land. This needs a whole raft of policies and actions to address the issues highlighted above. There are promising signs in the expansion of small towns and cities in rural areas of Africa, creating urban markets that can help support the diversification of livelihoods. Another positive development is the focus on regional markets through the African Continental Free Trade Area.

This is a problem that concerns us all. As we have seen, the goals of zero poverty and zero hunger go hand in hand, as the majority of the rural poor are small-scale farmers by default. The opportunity for agricultural development to support the broader development of African economies is clear, as is the need for concurrent job creation in other sectors. The rural population in Africa continues to grow rapidly, doubling every 20 years. Intensifying agriculture is therefore fundamental to preventing further land use change and conversion of natural habitats to agriculture. It is also fundamental to allowing current and future generations to earn a decent living.