Rethinking consumption

We cannot hope to tackle the climate crisis without a fundamental shift in how, what, and why we consume

Climate — Global

Environmental impacts like climate change and biodiversity loss threaten our future. Household consumption greatly contributes to these and other environmental impacts. But what should consumers do to conduct an environmentally friendly life? And what should policymakers do to incentivize sustainable consumption? Today’s economy offers countless options for consumption, so to consume sustainably is not at all a straightforward task.

For policymakers, it is essential to understand the drivers of consumption impacts. In multiple studies, income is identified as the most relevant driver of consumption impacts (Hertwich and Peters, 2009; Ivanova et al., 2016; Baiocchi et al., 2010; see also Figure 1). In addition to income, household size is acknowledged to play a significant role. Per capita footprints generally tend to decrease with household size, but this trend is less pronounced for high-income households (Froemelt et al., 2018; Underwood and Zahran, 2015; Weber and Matthews, 2008).

Households in dense urban areas in higher-income countries tend to have lower impacts due to less land-based mobility impacts (shorter distances to travel, more availability of public transport) and smaller apartments (Baiocchi et al., 2010; Tukker et al., 2010; Wiedenhofer et al., 2018; Froemelt et al., 2020). While it is difficult (or less popular) for policymakers to influence income and household size, urban densification can be influenced by urban development policies. However, the impact of location on consumption impacts is less evident than that of income and household size.

Figure 1: per capita impacts from 1995 to 2020 divided by income group countries. Data are based on the Resolved EXIOBASE3 database (Stadler et al., 2018; Cabernard and Pfister, 2021). Methods for the impact assessment according to UNEP, 2016; Boulay et al., 2018; Chaudhary et al., 2015.

Some studies also try to cluster consumer groups into archetypes, which by trend have smaller or larger environmental impacts. Such studies may help to develop targeted incentives or other political measures to lower the environmental impacts of particularly impactful households.

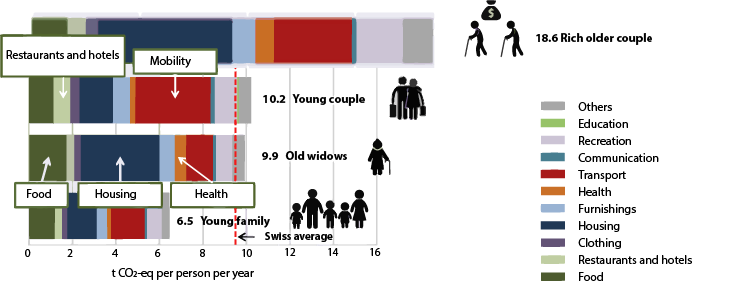

For example, a Swiss study (Froemelt et al., 2018) shows that the household group having the least per capita environmental footprint is young parents with small children, as they tend to have low-mobility impacts, low apartment area per person, and eat a balanced diet at home (Figure 2). Those who have a high footprint include:

- relatively well-off couples close to retirement age that live in over-dimensioned houses and spend much of their free time traveling

- young unmarried couples with high incomes who tend to travel and eat out a lot

Studies like this demonstrate that lifestyle – affected by income, age group, household size, and other factors – has direct implications on our footprint. But this is not everything. These studies also tell us that there are consumers that diverge from the general patterns. For example, research in Switzerland (Girod and de Haan, 2009) shows that low-impact households with comparably high income also exist. They tend to consume less mobility, live in houses with “green heating systems” (like heat pumps), and generally consume high-quality (higher priced) goods. Such households potentially serve as a model for others.

Figure 2: per capita carbon footprint of selected consumption archetypes (out of a total of 28 archetypes) in Switzerland (Froemelt et al., 2018).

What should environmental consumers do?

Life cycle assessment studies show that housing, mobility, and food are the most relevant consumption areas for greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (for example, Hertwich and Peters, 2009; Tukker and Jansen, 2006; see also Figure 1). For water stress and biodiversity loss (through land use or eutrophication, where water becomes progressively enriched with minerals and nutrients), food is the dominant consumption area (International Resource Panel, 2019; see also Figure 1). In industrialized countries, environmental hotspots for GHGs and biodiversity loss include:

- high meat and dairy consumption

- foods from tropical regions (such as cocoa and coffee; Chaudhary et al., 2016)

- food wastage

- personal mobility (especially driving cars and flying)

- heating homes with fossil fuels

From such studies, environmental recommendations have been derived such as “fly less” or “reduce food waste.” But if consumers follow some of these recommendations, does this make the footprint of their lifestyle better? Probably. But not necessarily.

This is because rebound effects may offset some of the environmental gains. Assume, for example, that a consumer reduces food waste to lower their environmental footprint and therefore needs to buy less food. This is good. But it may also save the consumer some money that they can spend elsewhere. This is usually referred to as the “rebound effect,” where a reduction in consumption (aimed at reducing the environmental impact) does not achieve its goal fully, because monetary or time savings induce further consumption and, hence, environmental impacts. For example, a UK study (Chitnis et al., 2014) shows that money saved by avoiding food waste is often spent on other consumption with comparable or even higher impacts. On average, for food waste reduction, approximately 80% of the initial GHG reduction saving is lost due to the impact of such alternative consumption.

So, are efforts to cut food waste reduction in vain? Should food continue to be wasted? Of course not. But we need to pay attention to what is done with the saved money or time, and to be aware of the risks of problem-shifting. In the end, it boils down to the question of how consumers spend time and money as a whole: making sure they are not just focusing on improving one consumption area and shifting their footprint from this consumption area to another.

Being aware of rebound effects is an essential start. In particular, as consumers, we can try to avoid high-impact activities altogether. Why not spend the holidays at a place nearby or, if further away, take more time to travel there by train or bike? Living in a well-insulated apartment close to our place of work reduces mobility and heating demand. Eating high-quality seasonal food with only a few animal products can improve both environmental impact and health. Such actions should preferably be combined and not be “either or.”

Consuming less also helps, especially when investing the saved money in activities, projects, and people that contribute to an environmentally friendly society. Renewable energies are a good starting point. Why not install solar panels on the roof or balcony – maybe together with neighbors? Or, if that’s not possible, perhaps look to buy shares in a bigger local photovoltaic plant run, say, by the city or other investor. In addition, we can support environmentally friendly producers or organizations that foster environmental protection. This may then have a positive influence beyond our own footprint.

This consumer-centric view should be regarded alongside systemic societal changes in our whole economy. These include transitioning to a renewable energy system and creating a circular economy. We need these to make producing consumer goods more sustainable. But only a joint effort in making both production and consumption more sustainable can make a transition towards a more environmentally friendly future happen.

Today, we are taught by marketing campaigns that buying more goods and services makes us happier. What is needed is a major rethink of consumption where we seriously evaluate which consumption really increases our well-being as opposed to consumption that we only believe is rewarding.

One such example is fast fashion. According to a German study, 50% of new clothing purchased in Germany is only worn once or twice before it is discarded (Greenpeace, 2015). Getting away from linear business models and changing marketing towards promoting high-quality, long-lasting products and services could play a big role here.

And would it not be timely for green influencers to emerge who show us how to “get more with less?” Policymakers need to act now and provide incentives for circular systems and long-lived products (and set limits to unsustainable marketing campaigns and products). It is time to rethink consumption altogether and to shift the focus to services and goods that really create well-being, while only having bearable impacts on the environment.