Less is more: plugging the climate financing gap

Funding for polluting projects remains alarmingly high. We need to urgently switch this finance toward sustainable projects. The relatively cheap cost of action now compared with the economic disaster of inaction is a math “no brainer” – and the time to act is now

Financing — Global

The stakes for climate action have risen ever higher this year, even as the window for action to lower the stakes has shrunk. The United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the world’s most authoritative climate science body and host to the world’s highest-level climate talk – the 26th Conference of Parties (COP26) – says that we are unequivocally headed toward climate catastrophe within two decades.

To counter this, all eyes are on global leaders’ efforts to mobilize increased quantities of climate finance, loosely defined as funding for activities that reduce emissions and/or increase climate resilience. Their immediate goal is to fulfill the USD 100 billion per year commitment that developed nations made to fund climate mitigation and adaptation needs in developing countries.

The Paris Agreement also prioritizes “making finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development” (Paris Agreement Article 2.1[c]). Yet the effort to mobilize USD 100 billion in climate finance is largely divorced from efforts to decrease negative climate financing for high-emissions sectors like fossil fuels. The bottom line is this: global commitments to climate finance at home or abroad cannot achieve Paris alignment or a 1.5ºC scenario until they are matched by proportional and science-informed commitments to decrease fossil fuel finance.

Net climate finance

To optimize the impact of each hard-fought dollar world leaders raise for the climate, climate finance tallies should integrate net climate finance totals in addition to absolute totals. The success or failure of finance mobilization efforts would then reflect a more accurate snapshot of global financing trends by indicating whether positive climate finance (defined by the Rocky Mountain Institute as finance for activities that reduce emissions and/or increase resilience) approaches or exceeds negative climate finance (finance for activities that increase emissions and/or reduce resilience).

Increasing net climate finance is undoubtedly a larger lift than increasing absolute climate finance. To be successful, public, private, and multilateral mobilization efforts will entail improved coherence across activities on both sides of the climate ledger, first to increase positive climate finance and, second, to reduce negative climate finance that undermines it.

This article summarizes the clearest steps for addressing the increasingly urgent priority of reducing negative climate financing totals, steps with the potential to unlock hundreds of billions to be allocated to fill positive climate financing gaps.

The cost of averting climate catastrophe

Estimates by the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network and World Bank suggest that the annual cost of achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) falls between USD 5 and 7 trillion. Of this, the latest IPCC cost models indicate that the world needs to spend at least USD 1.5 trillion per year to achieve global climate targets that align with a 1.5ºC scenario.

What is the climate financing gap, and how can the world fill it?

The current state of climate finance

As a category, sustainable finance lacks a universal definition or set of criteria. Broadly speaking, it refers to financing that flows to companies and projects that purport to align with the SDGs and/or meet a range of positive environmental, social, and governance (ESG) indicators.

The underlying integrity of sustainability and ESG-qualifying financing is limited by the shortage of quality input and reporting data. A proliferation of frameworks and governance structures are emerging to address this challenge (see p.66 and “Aligning business and finance with sustainable development” by Lisa and Jeffrey Sachs). Even so, it is undoubtedly trending upwards, reportedly accounting for roughly one third of global assets in 2020, amounting to over USD 35 trillion across Europe, the US, Canada, Australia, and Japan. These figures amount to a 15% increase over 2018 levels and a 55% increase over those in 2016.

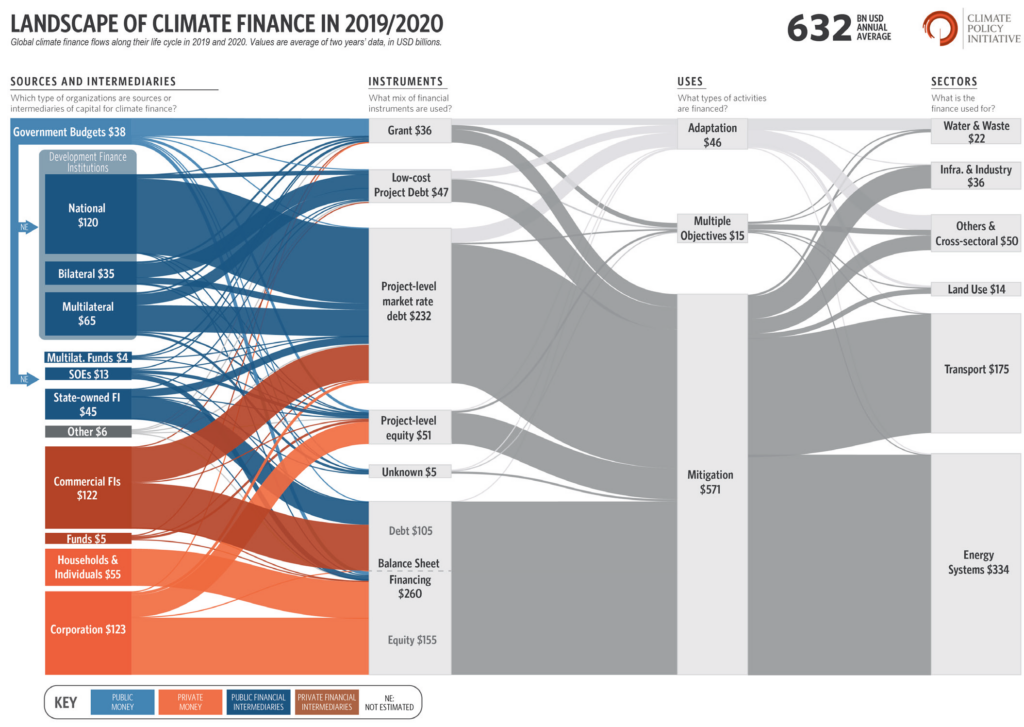

As a sub-category of sustainable finance, climate finance also lacks a standard definition with which all stakeholders agree. The Climate Policy Institute (CPI), which accounts for multilateral, public, and private climate finance, reports that positive climate finance is trending up, totaling approximately USD 632 billion in 2020. According to Pitchbook, global investors have already successfully raised as many climate-focused funds in 2021 as they had over the previous five years combined.

However, negative climate finance far exceeds it, with USD 781 billion going to fossil fuel companies from private banks. When accounting for multilateral banks, sovereign wealth funds, and private equity financing, negative climate financing totals are much larger.

A quick calculation indicates that 2018’s net climate finance was in the red, totaling minus-USD 241 billion. Now, in 2021, it continues to be heavily skewed toward unsustainable projects, so much so that the International Energy Agency (IEA) issued a stark warning in its 2021 World Energy Investment Outlook: “The USD 750 billion that is expected to be spent on clean energy technologies and efficiency worldwide in 2021 remains far below what is required in climate-driven scenarios. Clean energy investment would need to double in the 2020s to maintain temperatures well below a 2°C rise and more than triple in order to keep the door open for a 1.5ºC stabilisation.”

There is a wide range of policy and financial instruments that governments can consider for mobilizing the large sums necessary to fill the climate, and broader SDGs’, financing gap.

Skewing climate finance toward positive

By the end of 2021, over two thirds of global GDP will be generated in places with established or proposed net-zero emission goals. As measurement, disclosure, and accountability systems take root across the financial industry, efforts to ensure their transparency and rigor will help to increase accountability and drive reductions in negative climate finance. By taking the steps outlined below, national and corporate actors could unlock approximately USD 400 billion per year of current fossil fuel financing and reallocate it to positive climate channels.

1. End fossil fuel subsidies

As developed countries struggle to meet their USD 100 billion climate finance commitment to developing countries this year, a subset of these same countries continue to provide USD 88 billion annual subsidies to fossil fuels (of which the US accounted for USD 20 billion). Moreover, fossil fuel-intensive sectors received approximately USD 170 billion to respond to COVID during just the first eight months of 2020.

This year, G7 leaders reiterated their previous commitments to phase out “inefficient” fossil fuel subsidies by 2025, though there has been little progress to-date. The Brookings Institute is one of several respected institutions that has outlined recommendations for rich countries to dismantle their entangled networks of subsidies. Time is of the essence.

This could unlock upwards of USD 88 billion per year in global public finance for direct reallocation to fulfill developed countries’ USD 100 billion climate finance commitment to developing countries.

2. End fossil fuel expansion

The UN and IEA confirm that the world must end all fossil fuel expansion now if it is to meet its Paris Agreement goals. In spite of this, the financing community continues to drive the climate crisis, with banks still financing new coal projects even as they announce net-zero and sustainable finance commitments.

Banks have loaned or invested USD 3.8 trillion to fossil fuel companies and projects in the five years since global leaders signed the 2015 Paris Climate Accord, committing the signatories to reduce their carbon emissions by 45% by 2030 and net-zero by 2050. About USD 1.5 trillion of this finance, or approximately USD 300 billion annually, has gone directly to companies taking on the majority of new projects. To date, no major global bank has committed to phasing out its fossil fuel finance, nor has any agreed not to fund new fossil fuel projects that locks in emissions decades from now, when the world is meant to be decarbonized.

To mitigate this, national governments should legislate against new fossil fuel exploration and extraction activities on public lands, as the US has in the Arctic Refuge, and move to fine, tax, or otherwise penalize corporate actors who persist in financing unsustainable activities beyond their reach.

This could unlock upwards of USD 300 billion per year to reallocate as positive climate finance.

3. Increase the costs of negative climate finance

There are a range of tax interventions that lawmakers can levy on bad actors to disincentivize the volume of funds still flowing to fossil fuels and other negative climate targets. A globally coordinated carbon tax would be effective both in raising revenues for climate finance and in reducing emissions, as stated in an SDSN report on the SDG financing gap in 2019.

Carbon pricing initiatives currently cover 46 national jurisdictions and 28 subnational jurisdictions, representing 20.1% of global GHG emissions. These generated approximately USD 82 billion in revenue in 2018, according to the World Bank’s Carbon Pricing Dashboard. The annual emissions of high-income countries currently stand at approximately 40% of the world’s emissions, or roughly 14 billion tons of CO2 per year (IPCC, 2019).

If just USD 4 per ton were earmarked for positive climate finance, the revenues would amount to more than USD 50 billion per year. The estimated social cost of carbon is currently set by the Biden administration at USD 51 per ton, far higher than USD 4 per ton, and is a number the administration is expected to significantly increase.

4. Build up a positive climate finance constituency

Given the entrenched special interests behind public and private fossil fuel finance, civil society initiatives – like US-focused BankFWD, UK-based Make My Money Matter, and global Bank.Green – play an important role in growing constituent and consumer demand for politicians and banks that align their financing with the Paris Agreement.

Conclusion

The impacts of climate change will reduce global economic output by 11% to 14% by 2050, the equivalent of up to USD 23 trillion in losses.

Globally, governments have spent an estimated USD 16 trillion on the COVID-19 crisis. This has saved millions of lives. We now have an opportunity to save hundreds of millions of lives by committing just a fraction of this sum annually to finance a more stable, sustainable, and just future by endeavoring to limit warming to 1.5°C.

Do the math.