Getting everyone to act on climate change

The reasons for climate inaction are many and varied. We need a range of strategies to ensure that everyone – from the concerned to the skeptical – takes the action our planet needs to survive

Climate — Global

We need everyone to act on climate change, now. Despite growing concerns about climate change worldwide, only a small fraction of the population has taken action. How can we scale up climate action and collectively address the current climate crises?

For global challenges like climate change, no single intervention works for everyone. This is because people hold different, sometimes opposing, views on climate change, and their reasons for inaction are different. What we need, then, is a comprehensive set of interventions that target different subsets of the population, from the most concerned about climate change to the skeptics. It is critical that no one is left behind.

Social diffusion of climate action

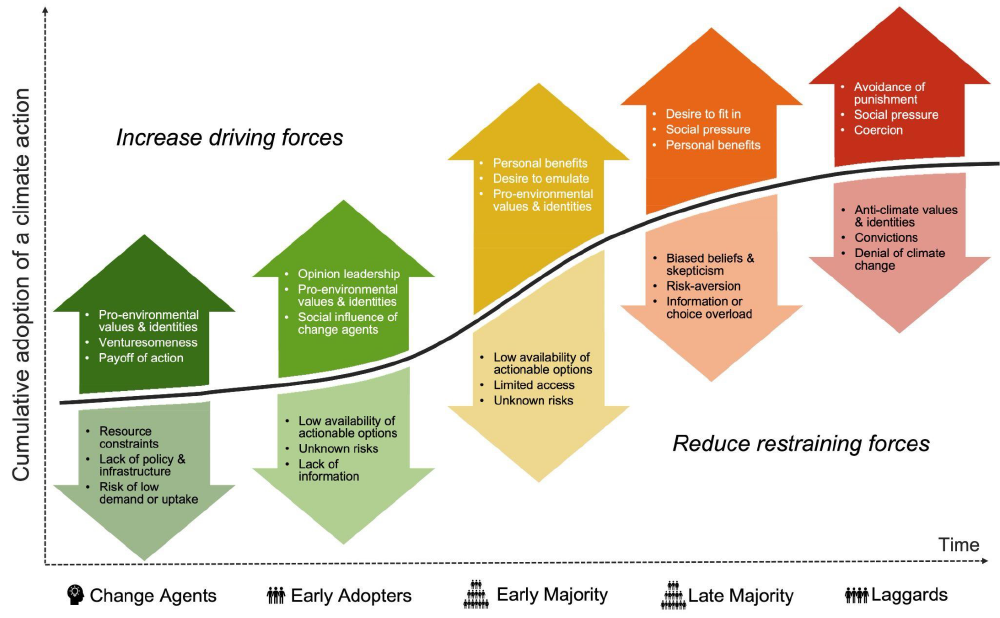

We propose an integrative approach that describes the diffusion of climate action across an entire population (see Figure 1). This approach provides a recipe for enabling a variety of climate actions, including private individual actions (such as flying less), social signaling actions (such as sharing climate change information), and civic actions (such as signing petitions). For a given climate action, this framework:

- segments the population based on the adoption rate of the action into distinct groups of people, from change agents, early adopters, and the early majority, to the late majority and laggards (diffusion of innovation theory)

- identifies the forces that drive and restrain the action within each group (force field analysis)

- proposes appropriate interventions to increase the driving forces and to reduce the restraining forces behind the action for each group

The approach offers a comprehensive set of solutions that target distinct groups of people within a given population. In the next section, we describe the distinct groups, the forces, and the interventions for scaling up climate action.

Figure 1: a social diffusion approach that identifies the key driving forces and restraining forces behind climate action for change agents, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards. Each force, indicated by a bullet point within a group, is separate from other forces, and can be changed by appropriate behavioral interventions.

Change agents

Change agents create conditions necessary for the widespread adoption of climate action. They include policymakers, activists, NGOs, and innovators of climate-friendly technology and products.

Change agents are driven by pro-environmental values and identities, venturesomeness, and the potential payoff of the action. However, their actions are restrained by the absence of resources, existing infrastructure and policies, and by the risk of low demand or uptake of their ideas or innovations.

Change agents can benefit from individual interventions that reinforce their values and identities, and systemic interventions that provide resources and policy support.

Early adopters

Early adopters are the first to adopt a climate action when it becomes viable (for example, the first ones to purchase a plant-based hamburger).

Like change agents, they are driven by pro-environmental values and identities, and by a desire to signal their fast adoption of the action to their social circles. These individuals are strongly influenced by change agents through personal, social, or professional connections. The restraining forces they face include low availability, unknown risks, and lack of information about the action.

To encourage early adoption, individual interventions include reinforcing values and identities and increasing social signaling power. Systemic interventions such as increasing availability and accessibility of the action, and disclosing its risks and information are most effective for this group.

Early majority

This group follows suit and engages in climate action promoted by early adopters.

However, its driving forces are different, involving personal benefits of the action (for example, health benefits or cost savings of eating less meat), a desire to emulate early adopters, and somewhat weaker pro-environmental values and identities. Those in the early majority group face similar restraining forces to early adopters: low availability of and limited access to actionable options, and unknown risks of the action. Change agents, early adopters, and those in the early majority make up half of the population.

For the early majority, driving forces can be enhanced by individual interventions that involve role model endorsements, reinforcement of values and identities, and social recognition for taking climate action. Restraining forces can be reduced by individual interventions that provide more information about the action, use ownership framing, or reminders. Systemic interventions include increasing the availability of and access to actionable options and disclosing risks of the action on a large scale.

Late majority

The late majority will adopt climate actions because they want to fit in with the rest (herd mentality). They also experience considerable pressure from their social networks.

Like the early majority, these individuals are partly motivated by personal benefits of the action. Their barriers include biased beliefs, skepticism from insufficient evidence, tendencies to avoid risks, too much information, and too many available actionable options.

To enable climate action in this group, individual interventions that use social norms, peer pressure, and peer influence can increase the driving forces. Reducing restraining forces involves providing information or social support from trusted sources. Systemic interventions can reduce restraining forces by providing incentives and rewards for taking climate action, making the action easy and affordable, making the action the default, disincentivizing inaction, and making non-climate-friendly options more difficult.

Laggards

The laggards are the most reluctant to act and the most resistant to behavioral intervention. Their resistance to climate action is due to strong values, identities, and convictions that challenge the validity of climate action and the reality of climate change itself.

Their eventual climate action is driven by the avoidance of punishment, significant pressure from their peers, and coercion through laws and mandates. For many of these individuals, their resistance to climate action is reinforced by the inaction of the people in their social circles who also hold similar values, beliefs, and convictions.

Individual interventions can use peer role models to deliver messages and to endorse climate action. Systemic interventions that involve mandates and penalties for inaction are better suited for this group. Those in the late majority and the laggards make up the remaining 50% of the population and are often overlooked by behavior change interventions.

Call to action

This approach offers a blueprint for practitioners, researchers, and policymakers to mobilize climate actions in ways that address the diverse motivations and barriers of each segment of a population. To prevent the worst effects of climate change, we should acknowledge the different groups of people, the distinct forces affecting climate action, and tailor interventions to each group.