Whose bioeconomy, whose knowledge, and whose profit?

The nascent concept of “bioeconomy” offers a new sustainable paradigm where economic growth supports nature rather than plunders it. Can bioeconomies genuinely transform regions like the Amazon, plagued by decades of resource extraction and exploitation, in the face of powerful, global, corporate interests?

Climate — Global

Bioeconomy is a multifaceted concept, under development and dispute. It’s seen by many as a key component of the future world economy, as humanity fights climate change and struggles to move away from fossil fuels through low-emissions development. However, to date there has been a lack of a shared understanding of bioeconomy between academic disciplines, policy sectors, and other knowledge systems. The direct economic impact of bio-based products, services, and processes is estimated to be around USD 4 trillion per year globally over the next 10 years.

Is bioeconomy inherently sustainable or fair? Not at all. Due to the lack of consensus on the term, there are risks associated with its use as a synonym for the green economy or as a panacea. These risks involve prioritizing low-value, high-volume products (such as sugarcane and other monoculture plantations) at the expense of low-volume, high-value chains and services (including ecotourism, pharmaceuticals, and superfoods).

History is a powerful witness and a teacher. In addition to the potential environmental harm of unregulated bioeconomy activities, playing by market rules can lead to biopiracy, elite capture, overexploitation of local people’s labor, and high value added to biodiversity products far from the hands of local producers and the lands from where such bioproducts originate. In this new bioeconomy wave, are we prepared for turning the key, or it is just going to be more of the same?

Since the 2010s, some authors have sought to present the field of bioeconomy from three perspectives: biotechnological, bio-resources, and bioecological. The bioecological vision brings a new sustainable dimension in the relationship with nature and at the same time in the integration of human life in this context. It provides a more systemic approach to the bioeconomy, including integration of sustainable production parameters, and innovative forms of production to reconcile land use and biodiversity conservation. It can generate opportunities for valorization and social inclusion of Indigenous peoples and local communities (IPLCs), and local family producers.

Challenges for Amazonian bioeconomies

Recently, bioeconomy has emerged as one of the most important vectors for a sustainable future for the Amazon. The promotion of an economy based on the potential of its rich biodiversity and local knowledge offers a compelling alternative to established models of a predatory economy. Some biotechnology and bioresource models developed through conventional market practices can compromise the rights and well-being of IPLCs in the Amazon, where local livelihoods, rural–urban dynamics, and socio-cultural identities are products of intricate social–ecological connections and flows.

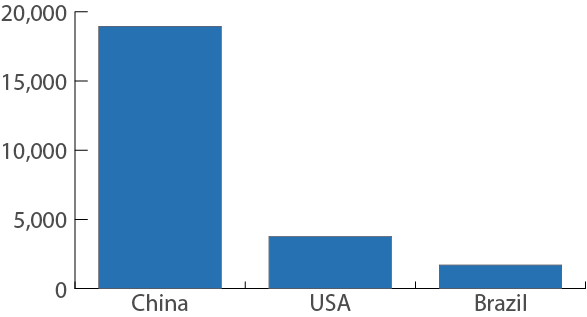

Unethical access to IPLCs and global use of biodiversity compounds is happening in an escalating manner. For example, large international corporations abroad dominate patent applications for innovations from Amazonian biodiversity. Around 43,000 patents for innovations with the Amazon flora had been filed worldwide by 2022, with significant leadership from China and the USA, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Number of patents for Amazonian botanical products designed by companies filed by 2022

Source: Adapted from Adeodato, S. Corrida das Patentes, Biodiversidade, Valor Econômico, 2023

Many industrialized countries, due to their academic capacity, technological infrastructure, and resources, dominate the main industries for transforming biodiversity resources. Less-developed countries, meanwhile, play the role of suppliers of primary inputs, without adequate remuneration for the genetic, natural, and social capital acquired from IPLCs.

A series of regulations have increasingly sought to protect and, at the same time, give due value to the collective knowledge of IPLCs, who have co-evolved with Amazonian biodiversity since time immemorial. Despite the worldwide adherence to the Convention on Biological Diversity and the Nagoya Protocol, only a few countries have established local policies, most of them in the Global South. These countries face great difficulties in policy development and implementation, with significant differences among them in terms of regulations around benefit-sharing of access to genetic patrimony and traditional knowledge.

In 2015, Brazil established its Biodiversity Law to regulate access to genetic heritage and to associated traditional knowledge. Despite the law, there are still a series of challenges in its implementation. For example, a recent report found that only 9% of the registration of new biodiversity-based products by the Brazilian Ministry of the Environment included access to traditional knowledge in their scope. This reduces the possibility of increased benefit-sharing with IPLCs. The economy of “socio-biodiversity,” the most widespread term in Brazil, includes the dimension of the diversity of socio-cultural systems. The term socio-biodiversity was defined in 2009 by the Brazilian National Plan for the Promotion of Socio-Biodiversity Product Chains (PNPSB) as a “concept that expresses the interrelationship between biological diversity and the diversity of sociocultural systems.” The so-called “economy of socio-biodiversity” or “socio-bioeconomy” is a proposal to enhance “the economic manifestations of traditional peoples and communities that are based on an inseparable relationship with nature, surrounded by respect and socio-cultural interaction with ecosystems and biodiversity, valuing different production and reproduction strategies, and based on the sustainable use of biodiversity” (see ‘Policy recommendations for the development of the economy and sociobiodiversity’).

These approaches, highly applicable to territories such as the Amazon, seek to highlight the socio-cultural aspects involved in any process of transition of production models, with the socio-productive inclusion of vulnerable populations. Additionally, investments, policies, and safeguards underpinning socio-bioeconomy initiatives should reinforce sustainable and just values and the principles promoted by several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including:

- No poverty (SDG 1)

- Good health and well-being (SDG 3)

- Gender equality (SDG 5)

- Reduced inequalities (SDG 10)

- Sustainable cities and communities (SDG 11)

- Life on land (SDG 15)

- Peace, justice, and strong institutions (SDG 16)

Regarding gender, a recent report produced by the Amazon Partnership Platform (PPA) found that 75% of impactful, community-based businesses mapped in the Brazilian Amazon had women in leadership positions and included gender issues in their portfolio’s assessment.

Toward bioeconomies of equal partners

The significant evolution of the socio-biodiversity economy will depend on the effective promotion of science and innovation. This should be based on a new approach of intercultural knowledge equity. We need to focus on generating quality of life for urban and rural residents through plural valuation, conservation, and sustainable use of Amazonian biodiversity. We need investment not only in research and development, but also to support and provide technical assistance to guarantee the viability of local businesses. We need business models that expand the capabilities of IPLCs to produce their own products and services by respecting their self-determination, rights, local lifeways, and values, and promoting good quality of life and well-being under their own terms.

To this end, sustainable, territorial development policies must promote technological innovations that provide the structuring conditions, such as water security, health, education, internet access, logistics, and transportation, combined with innovation hubs.

Moving from business as usual toward just and sustainable Amazonian bioeconomies will require equitable forms of knowledge articulation and exchange between IPLCs, science, and policy. Indigenous peoples and local communities must become equal partners in the planning, construction, and management of socio-bioeconomies’ policies and businesses, and not just as suppliers of knowledge and products in value chains.

Featured in:

Climate Action edition 2023: Taking stock

COP28 will be responding to the first Global Stocktake – a comprehensive assessment of our progress towards the goals of the Paris Agreement. That progress is too slow and, as our prospects of keeping within the 1.5°C target slip away, the emphasis shifts from mitigation to adaptation. With it, the focus moves to the Global South, which will suffer the worst impacts and lacks the resources to adapt. Climate justice and ‘loss and damage’ will take center stage.

This edition presents a range of actionable approaches to mitigate and adapt to climate change. The solutions offered are framed in the context of the SDGs and delivering climate justice.

Authors include Helena Viñes Fiestas, Tim Clairs, Phoebe Koundouri, Cassie Flynn, Olufunso Somorin, Maria Outters, Simonetta Cheli, Ibrahim Thiaw, Yamide Dagnet and Vanessa Ushie.

Publication date: 29 November 2023