The business case for the SDGs – what will the tipping point be?

To transform our world, the SDGs must also transform business. With just seven years left to the deadline, we must explore bold, new ways to encourage companies to genuinely engage with the goals and embed sustainable, climate-friendly practices for the long term

Business — Global

The corporate world is eager to engage with the SDGs. Globally, Google data shows a steady increase in searches for “Sustainable Development Goals” over the past five years. Anecdotally, the number of clients I hear mentioning the SDGs, sometimes very early on in a strategy development process, feels like it is growing month to month.

The high-profile Conference of the Parties has certainly helped drive awareness of sustainability issues like the climate crisis. Meanwhile, knowledge of the ins and outs of the 17 SDGs, at both goal and indicator level, has burgeoned dramatically. The 16,000 business signatories of the UN Global Compact have access to online business hubs and tools, as well as local networks linking business with civil society and government.

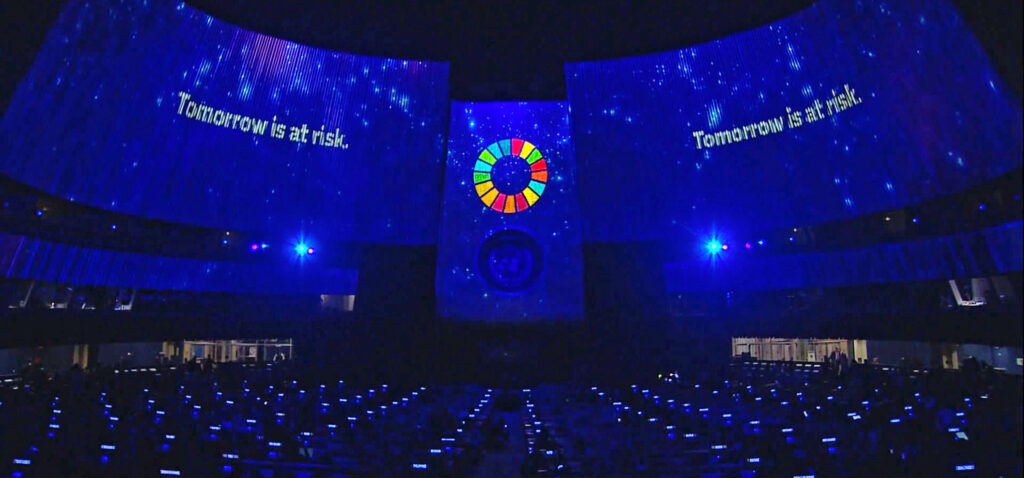

But with all the tools available, all the interest demonstrated, and all the genuine passion for this important international framework, there is still significant pace to make up for businesses to be truly aligned with the SDGs. In a world where greenwashing is the newest slur to be levied at business, with companies facing legal action for making green claims that cannot be substantiated, the SDGs seem like the unruly cousin – an unregulated, opt-in, no-repercussions framework. No one is going to hold a chief financial officer’s feet to the fire if they haven’t achieved the alignment goal they set for SDG 3. At the same time, there is nothing to be lost in demonstrating to investors and other stakeholders that your business is au fait with the goals by placing a roundel on your corporate communications. “Rainbow-washing” – the name for greenwashing when it applies to the SDGs – is heard in the corporate world more and more frequently, but there are as yet no legal or financial ramifications for doing it.

Both too open and too closed

The SDGs are like motherhood and apple pie. Everyone likes the concept: the 17 goals are wide-ranging and horizon-broadening, and they are hard to disagree with. It is difficult to state, at any level of a business, whether you are an intern or the CEO, that you are opposed to ending global hunger. That wouldn’t go down well by the water cooler, or in the global Zoom room. And yet, it is relatively abnormal for companies to engage with the SDGs at a deep operational level – in a way that engages with business growth, research and development, innovation, transformation, and that fundamental shift needed towards new, greener, more socially oriented, and sustainable economic markets. Instead, businesses tend to pick the SDGs that their operations are closest to. They tie the goals into their already-existent sustainability strategy, and hope their efforts in that direction will naturally have an impact. This is a good start. One would hope that, having linked SDGs into their sustainability frameworks, the goals would naturally feed upwards into a business’s operations.

But it is not so simple. Strategies are nothing without key performance indicators and targets, and getting down to the indicator level of the SDGs is where businesses often find their first hurdle. There are 231 unique indicators that sit underneath the 17 SDGs, and the way that they are scripted does not always allow business to meaningfully engage.

For an agriculture business which has, in theory, a close relationship to SDG 2 (end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture) it may be impossible to feel that there is meaningful contribution to be made to any of the indicators, which measure elements like:

- prevalence of undernourishment (2.1.1)

- presence of anaemia in women (2.2.3)

- agricultural export subsidies (2.b.1)

It is very hard to engage with SDG 17 (strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development) unless you are a government, non-governmental organization, or international finance body. And that is because the SDGs were built through complex, long-form international negotiation and diplomacy with many actors. Businesses were far from the core players, and the outcomes were not designed only to engage them.

This does not mean we need to start from scratch. While the issues outlined above might feel far from a business’s day-to-day activities at first blush, it is almost certain that such indicators are stored up in their supply chain. Somewhere in those 231 indicators, most businesses should find something to which they can meaningfully contribute. Indeed, firms may find that the exercise helps them to think laterally and holistically. How could a manufacturing business meaningfully contribute to 1.4.1 – an increase in the proportion of population living in households with access to basic services?

Perhaps, if they were a kitchenware manufacturer, they could donate some of their excess stock to community groups whose basic needs are not currently met. Or they could keep a percentage of goods at low enough costs for such groups to access them on an ongoing basis. Both are potentially exciting outcomes for a business to consider and in doing so in line up with wider thinking about the role of businesses in wider communities, and variations of stakeholder capitalism.

Currently, the former activity – donating goods – would likely be characterized under a standalone charitable initiative. The latter activity would form part of a pricing strategy. But neither would involve operational change. Should the prompt from the SDGs really be towards these short-term, initiative-led approaches? Or should it indicate instead more transformative change, supporting firms – and so, our economies – to move in a long-term direction, radically shifting their operations to support sustainable development?

This “investigate-the-indicators” methodology is a high-friction, high-investment approach to the SDGs. It involves deeply combing the indicators for something that might not be evident, and may not be operationally important. Will the kitchenware manufacturer find indicators across multiple SDGs? Will they be able to respond to the interconnected manner within which the SDGs should be realized? And are there genuine contributions to be made to the achieving of the SDGs that firms may be able to provide, but are not currently captured in existing indicators?

As a default outcome, then, businesses are often left with top-level alignment, and little room for maneuver underneath. The SDGs at goal level are open enough for any business to argue that they have considered them within their planning. But in their granular, indicator form they are too closed for firms to feel like they can genuinely contribute.

What happens next?

There are seven years left until 2030, when the clock runs out on the SDGs and we look to the next generation of the framework. In those seven years, I believe we need to be more experimental to draw the power and finance of the private sector into the SDGs’ vision. These experiments would be usefully focused on business operations rather than initiatives, and on long-term transformation rather than short-term impacts.

One experiment could be to promote the hooking of the SDGs into the innovation, research and development, new business, and sales and marketing functions of business, drawing them into the strategic center of business activity. The same approach has proven valuable for the wider sustainability or ESG (environmental, social, and governance) drive within business. How would a new product or service offering be developed if it was to be targeted at SDGs 4 and 9? How would design teams react if they knew the customer demographic particularly valued SDG 7? Using the SDGs to shape out a new business canvas, rather than retrofitting it into existing activities, could lead to transformational outcomes.

A second experiment here is to develop a secondary set of indicators, diversified from the current suite, that are actionable for the private sector. These should be more open than the current indicators and give specific guidance to different sectors to help them work towards the goals, galvanizing work towards, not just alignment to, the goals. Co-creation with business could lead to peer learnings and deeper buy-in for the SDGs, and gain insight from the business community – all useful as we look towards 2030.

A third route could pick up the legal fight. There is a role for the SDGs in state and region-level business legislation, to make the legal risk that accompanies greenwashing real for rainbow-washing too. The recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures, a mandated reporting requirement in the UK from 2022 for companies of a certain size, has shifted climate risk and opportunity to the mainstream, and is an example of where regulation has moved the dial on strategy. Some nations have already embedded the SDGs into investment policy. Scotland is a good example of this being done within the context of nationwide innovation and development, with the SDGs at the heart of its National Performance Framework.

Extensive work has been done to embed the SDGs in places where the barrier to adoption is low, and interest is high – in academia, education, and the charities sector. Business, with its high contribution to global emissions, and its footprint on employment, the economy, and the natural world, should be the designated focus for the next seven years. It is the power and the potential of this challenge that keeps me working with businesses on the SDGs.