Spatial planning for land-based policy objectives

Action-oriented maps and data are critical to tackling the biodiversity and climate crises

Climate — Global

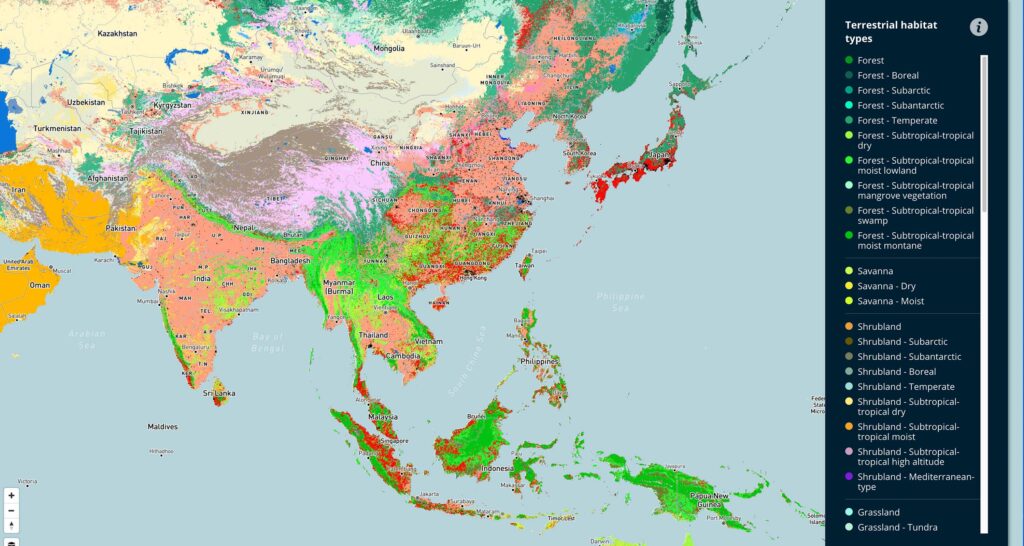

To meet the ambitious objectives of the upcoming biodiversity and climate conventions, integrated strategies need to be implemented to better manage land use for agriculture, infrastructure, biodiversity conservation, climate change mitigation and adaptation, water provision, and other services.

Governments need spatial data to identify which land areas have the potential to generate the greatest synergies between conserving biodiversity and nature’s contributions to people. The absence of action-oriented maps in land-based policies is concerning because neither the biodiversity nor climate crisis can be addressed without spatial data and spatial planning.

There are emerging policy actions on nature and climate happening around the world that require a spatial lens

These include the High Ambition Coalition’s 30×30 target to protect at least 30% of the world’s land and ocean by 2030 and the Leaders Pledge for Nature signed by 88 heads of government committed to reversing biodiversity loss by 2030. A recent study by the Nature Map Consortium presented an approach for integrated spatial planning to achieve policy objectives, which can provide support to decision-makers in prioritizing locations for conservation efforts. It shows that managing a strategically placed 30% of land for conservation could protect 70% of all terrestrial plant and animal species, while simultaneously conserving more than 62% of the world’s above and below ground vulnerable carbon, and 68% of all clean water.

Developing national maps for integrated land-use planning can have many policy uses, including generating finance for natural climate solutions, improving carbon markets, and greening supply chains

For instance, businesses need guidance on current and future land uses to understand from where they can and cannot source soft commodities, such as soy or beef. The same spatial data could also strengthen emerging standards for nature-related targets, as developed by the Science-Based Targets Network and the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures. As governments start to include action-oriented maps in their national climate and biodiversity strategies, countries can address several critical policy needs. These include ecosystem services valuation, clarifying land ownership and tenure issues, protecting land rights of Indigenous peoples, as well as incorporating key monitoring and evaluation tools for current and intended land use.

Spatial data and planning are not the sole answer to these global challenges; they are, however, a necessary step in advancing policies that meet national and local land-use objectives

Such land-based policies need to be designed in support of practical, local projects on the ground that both reduce biodiversity loss and anthropogenic emissions. This means that they need to be aligned with climate and biodiversity strategies to operationalize and meet the objectives of the UN Climate Change Convention and the UN Convention on Biological Diversity.