Investing in nature: a critical element in Australia’s efforts on climate action and sustainability

Australia has a significant opportunity to be a solution provider in nature-based investment. However, the present economic system does not include the value of ecosystems, despite the fact that ecosystem health is essential to our very survival. An Australian program seeks to address this challenge

Climate — Global, Pacific and South-eastern Asia

Humanity relies on our land and oceans to provide us with the food we eat and the fresh water we draw to irrigate our crops. Natural systems are home to a dazzling diversity of life that collectively contributes to and supports key planetary processes. However, the pressure on these systems is becoming extreme, and this will profoundly affect human progress and well-being.

The scientific “planetary boundaries” concept identifies nine limits within which humans can continue to survive and thrive, including climate change, biodiversity, and land system change. With four of those nine boundaries now crossed because of human activity, we need to fundamentally change the way we value nature. Protecting and restoring natural systems is essential to achieving many, if not all, of our Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Figure 1: The planetary boundaries

Building a new relationship with nature by investing in natural capital

Our land and oceans are unique, because unlike other systems, activities on land and in the ocean are both a source of greenhouse gas emissions and a potential solution to the climate crisis. They represent one of the biggest opportunities for slowing and turning around climate and ecological breakdown.

Increasingly, key elements in our land and ocean systems are being referred to as “natural capital.”

Natural capital was first referred to in the 1970s, becoming widely used by ecological economists from the 1990s. It is most commonly defined as the world’s stock of natural resources – which includes geology, soils, air, water, and all living organisms – and the services they provide. There are many types of natural capital that provide goods and services for people. Mangrove ecosystems are a great example. Pound for pound, these dense coastal forests store more carbon than land-based tropical rainforests, as well as providing breeding grounds for marine biodiversity and protection against extreme weather events. These natural assets therefore represent a major opportunity to achieve climate outcomes and many of the SDGs.

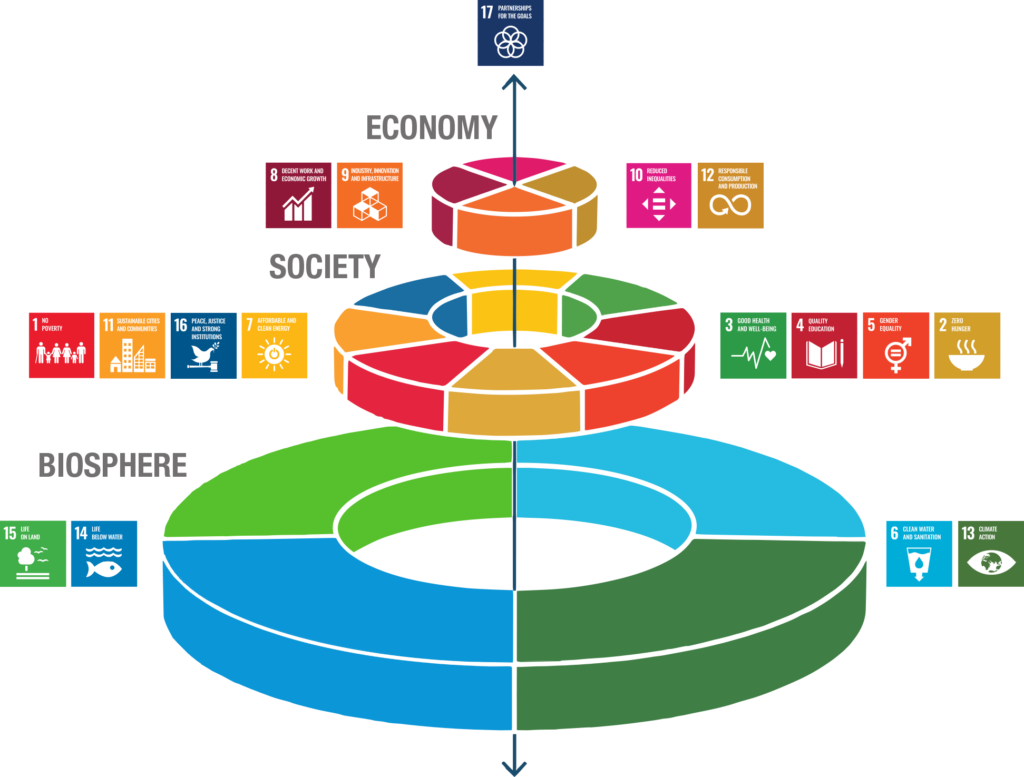

Yet traditional economic thinking has failed to take account of the rapid depletion of the natural world and all the goods and services that nature provides. Our present economic system does not include the value of our ecosystems or the concept of investing in nature. Australia has an enormous opportunity to be a solution provider in nature-based investment. The ability to measure and value our “natural capital” has been identified as a key solution for achieving future sustainability goals. As demonstrated by the Stockholm Resilience Centre in the figure of the “wedding cake” (Figure 2), achieving a number of the SDGs will depend on increasing the stock of natural capital both on land and at sea.

Figure 2: The dependence of the SDGs on our biosphere

Our biosphere can be viewed as the planet’s natural capital. Enhancing natural capital and the flow of services it provides is essential to the SDGs in the upper layers.

How can farmers measure their natural capital?

One of the biggest challenges we face is around incentives and new financing solutions for the enhancement or maintenance of natural capital.

While most land managers and farmers recognise the need to protect different types of natural capital, like trees, water resources, and the soil underpinning their production systems, the time and cost required to do so is often a barrier. It can also be hard to see the benefit of protecting natural systems on their properties without incurring significant cost or loss of income. Financial institutions and major businesses want to ensure that land is being managed sustainably and have a strong interest in developing new financial instruments that incentivize land managers to better manage their landscapes.

The measurement of natural capital is a crucial step on the path to develop new financing solutions. Proper measurement can help land managers to understand the state of natural capital assets on their land and demonstrate to investors, buyers, and consumers of agricultural products how these assets are improving over time. Measurement could enable the provision of new sustainability-linked loans for land managers who improve natural assets on their land and in turn provide benefits to the wider community.

Worldwide, there are many programs in development which focus on measuring and accounting for natural capital. For farmers and land managers on the ground, however, this poses a risk of inconsistent approaches or duplication of measurement methods, which could lead to a confusing market and a burden on land managers. Added burdens of time and cost of natural capital measurement can also make it difficult for farmers and land managers to even begin to work out how to access financial incentives and environmental markets.

Natural capital measurement programs currently exist. However, they are often focused on a single element of natural capital (such as carbon or biodiversity) or differ in their underlying measures and methodologies. There is a need for a harmonised framework that enables consistent measurement. The Natural Capital Investment Initiative (NCII) in Australia is seeking to overcome this challenge, with the development of a new and unique resource. Titled the Natural Capital Measurement Catalogue, this resource outlines a comprehensive set of natural capital measures for farmers and land managers to measure the natural capital on their property.

Incorporating a diverse range of sources and perspectives, including government, food supply chain, industry bodies, financial institutions, research, agriculture technology providers, and certification programs, the catalogue aims to create a common language for more consistent natural capital measurement at scale. While it is comprehensive, covering all elements of natural capital, the catalogue is also designed so users can easily identify and use only the specific measures that suit their individual objectives. The catalogue also acknowledges that farmers and land managers have different levels of resourcing to measure natural capital. It therefore covers a range of methods for specific measures, and supports users to increase the sophistication of their measuring over time. The catalogue will be piloted on farms to demonstrate how measurement of natural assets can be linked to new financial incentives.

Natural capital is fast gaining the attention of governments, corporations, and major financial institutions alike, with organisations looking to become more “nature positive.” The recently launched Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) will soon require organisations to incorporate nature-related risks and opportunities into their decision-making processes. The Natural Capital Measurement Catalogue will play a critical role in ensuring the Australian market is ready for such requirements, and will also share lessons learned on natural capital and its role in sustainable food and land use systems with the rest of the world.

Footnote: The Natural Capital Investment Initiative (NCII) is being led by ClimateWorks Australia (working within the Monash Sustainable Development Institute), supported by the National Australia Bank. NCII forms part of Land Use Futures (LUF), a multi-year program that is working to develop analysis and advice on what a sustainable food and land-use system looks like for Australia and how it might be achieved. Land Use Futures is connected to the global Food and Land Use Coalition (FOLU) led by the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network, World Business Council for Sustainable Development, World Resources Institute, SYSTEMIQ, and others.